“We kids got stung our share the first few years when we had bees. We would always lift the cover off the box to see how much honey they had made, but we finally learned. My Mother used to do this too. She always had long hair, into which she would get a couple of bees every time she did this, then she would run around the yard all she was good for, to get rid of them. I can still see her, it sure was funny, slapping at her head at the same time, to chase away the bees.”

I never met my great-grandmother, but I can see her clearly through my grandpa’s words. Curious and daring to open that box of bees, with a sense of humor, knowing well that she would soon be running around the yard in hysterics. Then, with the last bee gone from her hair, she would collapse from exhaustion, trying not to smile, but giving in at first glance of her children rolling in the yard, laughing.

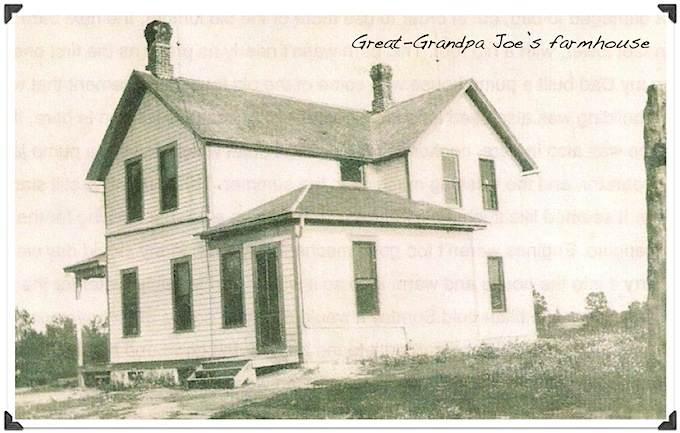

That moment in the early 1920s on a farm in central Minnesota is more than a family memory. It is a reminder of a time when people were closely connected to the sources of their food, brushing bees from their hair and removing stingers from their arms. A time when almost everything in their kitchen – milk, eggs, beef, pork, chicken, corn, grains, apples, plums, chokecherries, juneberries, black walnuts, and even honey – was produced on their farm.

That connection to our food is as much a part of the past as that moment in my grandpa’s memory. Most of us now have no idea where or how our food is grown and produced. Where that honey we drizzle on our toast originated.

“Dad's hobby was raising bees, this he sure enjoyed doing. He'd have as many as 25 hives. We always had all the honey to eat that we wanted. It got pretty sticky around there in late fall when he'd take the honey away from the bees and put it into fruit jars, although he had a lot of it in pound boxes*. This was called comb honey.”

*Langstroth hives“Dad's hobby was raising bees, this he sure enjoyed doing. He'd have as many as 25 hives. We always had all the honey to eat that we wanted. It got pretty sticky around there in late fall when he'd take the honey away from the bees and put it into fruit jars, although he had a lot of it in pound boxes*. This was called comb honey.”

My great-grandfather, Joe, was the only one of his brothers to keep honey bees, so the hobby may not have been passed down from his father. Instead, he probably experimented with a single hive at first, enjoying the short breaks away from the monotony of milking cows and working the fields. His love for beekeeping undoubtedly came that first fall when the family tasted the sweet honey, and saw the impact the bees had on the fruit harvest.

“Another thing my parents were proud of was their big orchard. They sure had reason to be. They always had so many apples, and also plums, really big ones. There were so many different kinds of apples too. Some would ripen early, others late in the fall. It was pretty near two weeks work for Dad to pick all those apples, although he enjoyed every minute of it.”

A swarm of bees in May is worth a load of hay; a swarm of bees in June is worth a silver spoon; a swarm of bees in July isn't worth a fly.

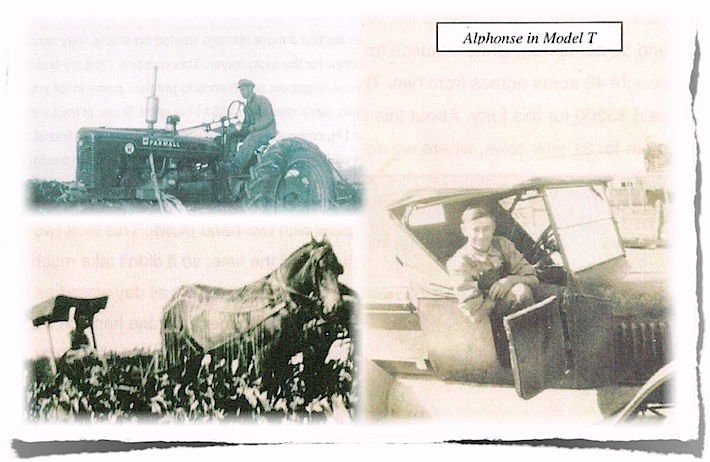

A famous beekeeping saying that my grandpa, Alphonse, learned from his father. A saying that my great-grandfather probably repeated to my grandpa when he asked for a hive to start beekeeping in the early 1940s – after he married, had a farm, and planted his own apple orchard.

The saying refers to the process of swarming. Every spring, most mature bee colonies will produce new queen bees in order for new colonies to form. Since there can only be one queen bee per colony, the original queen bee will leave, taking with her more than half of the bees from the original colony. This prime swarm will gather in a tight cluster, usually in a tree or around a tree branch near the original hive. The cluster will remain in this spot for a day or two while a few dozen female scout bees each search for a location for the new hive. When each scout returns, they will promote their site by literally having a dance-off (waggle dance). The more excited the scout bee dances, the more convincing she is to the other scout bees that she has found the ideal location. When they reach a final decision, the swarm flies off to the place and builds the new hive.

After the prime swarm has left, the new queen bees will start to hatch in the original hive. The first to emerge will most likely form another swarm, but taking a much smaller number of bees with her. This afterswarm may be followed by another afterswarm, and so on until the original colony cannot afford to lose any more bees.

Swarms that occur in May have more time to grow their colony and gather nectar, leading to a larger production of honey. Therefore, May swarms are the most sought after, followed by June swarms. Any subsequent swarm, as the saying goes, isn’t worth a fly.

I can imagine that cool, spring May morning in the 1940s when my grandpa first put on his beekeeping suit, thinking about the number of times he was stung as a child. My grandma watching through the kitchen window as he walked out of the house, turned, and smiled through the netting that draped over his large hat, covering his face. When he passed the barn, he probably startled the cows, the sound of their moos raising a tone at the end as if asking each other a question. He had been waiting for this day, finally spotting the prime swarm wrapped around an apple tree branch in the orchard earlier that morning. He slowly approached the swarm of 20,000 honey bees, and reaching for it with a broom, he would knock the clump of bees down into an empty pound box – where the bees would establish their new hive.

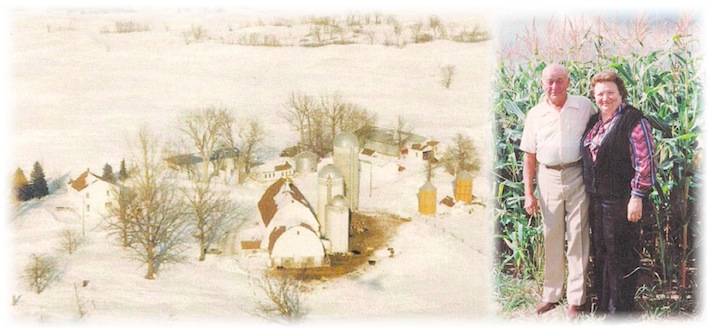

If an afterswarm occurred in May or June, he would be back with the broom to start another hive. Most summers having three colonies – the original colony, the May prime swarm, and the June afterswarm. As the summer progressed, the worker bees collected nectar, produced the honey in their stomachs, and stored it in the wax honeycombs on the bottom frames of the pound box. As the frames were filled throughout the season, my grandpa would add more frames, and then additional pound boxes when needed.

In the fall, he would be back with his beekeeping suit on, and a smoke torch. The smoke would drive some of the bees away, and pacify the others. But he had to be careful not to use too much smoke – as he was guilty of doing more than once – or the honey would have a bitter smoky taste.

Once the frames of honeycomb were removed, they were scraped into a big cooking kettle. Being careful to control the heat so as not to burn the honey, my grandma cooked it until the beeswax floated to the top and the honey settled on the bottom. The beeswax was then skimmed off and used as a sealant for canned fruit jam (just like bees do, when they use the wax to seal over the honey in the honeycomb). The honey ended up on toast for breakfast, and sometimes mixed with peanut butter as a special treat for the kids.

Once the honey was harvested, my grandpa would only keep the most productive colony, leaving them in their hive box on the sunny south side of the porch with a few frames of honey to eat over the long Minnesota winter. Then when the snow was gone in the spring, he moved the box back to the apple orchard to start all over again.

Unlike my great-grandfather, my grandpa never grew his beekeeping hobby beyond a few colonies every summer. And when he built a new house, and his apple orchard had to go, so did his bees. Time went on, farming and family took priority, and he never found his way back to beekeeping. Nor did his children, ending a short-lived, but important tradition in our family.

This Saturday, it will be four years since my grandpa died at the age of 92. I hope that one day I can honor him, and the great-grandfather I never met, by getting stung a few times by my own bee colony. To carry on a lost family tradition; to take a step toward connecting to the source of my food; and to keep the memory alive of two of the hardest working men who just happened to have a soft spot for a bee stinger.